Harare, Zimbabwe – The University of Zimbabwe’s University, the oldest and most prestigious university in the country, have been dismissed. Their wages, eroded by inflation and the devaluation of money, could no longer cover their basic needs, they said.

It was in April, and there is not yet a sign that they will return to their conference rooms.

“We have been betrayed and we have no more passion for our work,” said JT, a professor who has taught university for more than 10 years. He asked to be identified only by his initials for fear of reprisals from the institution.

The indefinite strike left thousands of students in difficulty. Many are trying to study for themselves, but do not know if their teachers will never return to work.

The University of Zimbabwe registrar’s office has not responded to a request for comments from a global press journal. But in May, the office published a statement saying that the problems that the teachers had raised were legitimate and that the university works with the government to resolve them.

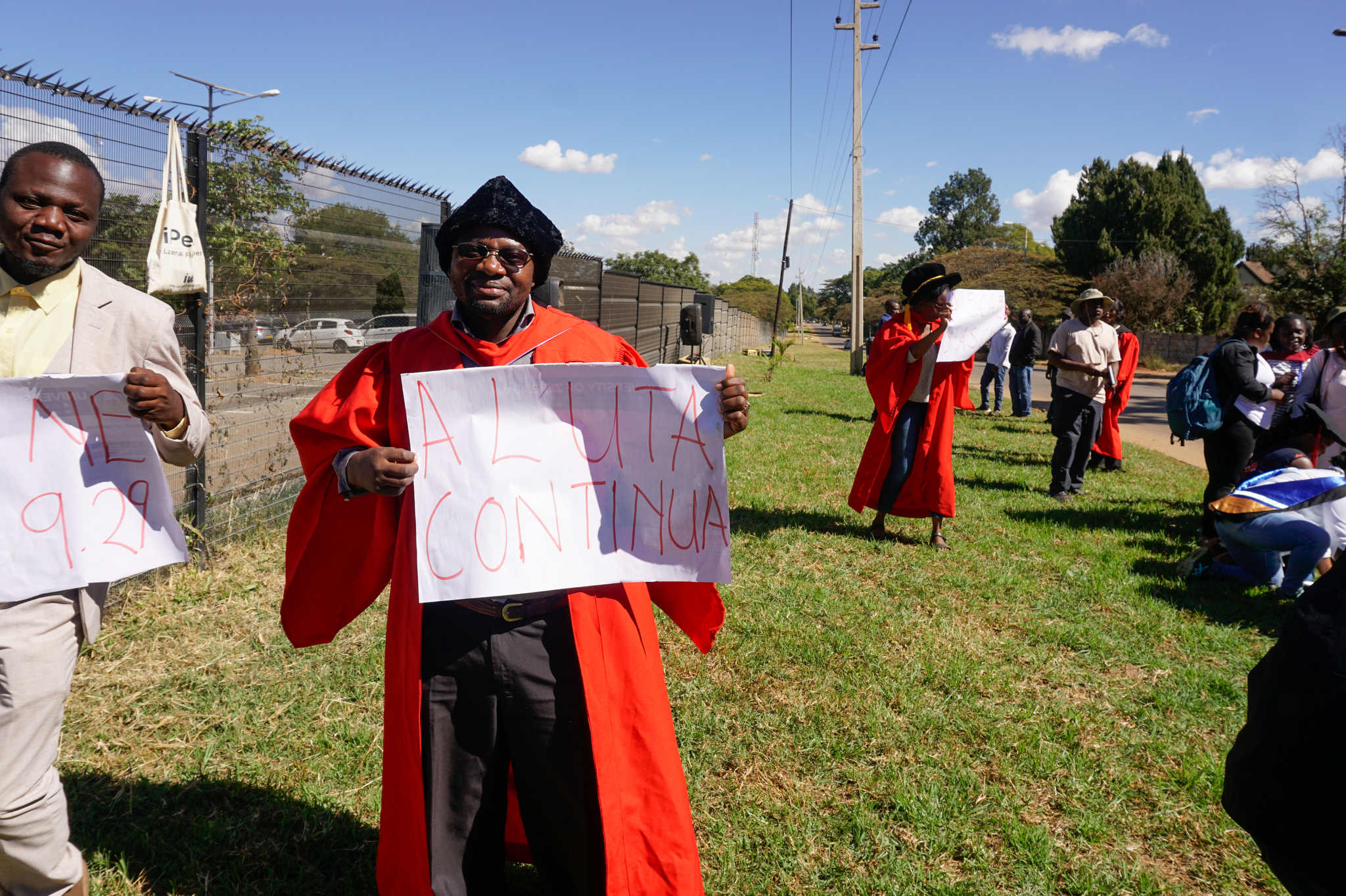

However, obvious Vegeyi, professor and spokesperson for the association of University Teachers, said that in June, the University rejected it as well as three other executive members of the association. All had headed the strike. The university, he says, also hired auxiliary teachers to fill the gap left by strike teachers, and some contract teachers have returned to work.

Narshon Kohlo, president of the Zimbabwe National Students Union at the University of Zimbabwe, says that it is only a Stopgap measure – who fails students.

“Some of them are only recent graduates,” he said, adding that they lack experience to adequately fill the gap. Students who started the semester with their regular teachers were left without continuity, and not all were assigned to replacements.

The problems extend beyond the university. The country’s economy in difficulty has dug many of its institutions. Hospitals are faced with worrying shortages of medicine and staff. Primary and secondary schools have trouble retaining teachers. And the higher education system of this sector, once a model on the continent, now loses its base.

Years of hyperinflation, instability of currencies and the decline in government support have stripped the institutions of resources, reduced wages and professionals in the country. Experts are concerned about long -term damage which could cause a country already struggling with economic collapse.

“If you destroy the education system, you have destroyed the basics of a viable and sustainable economic system,” explains Eldred Masunungeure, political scientist.

A defeated inheritance

In the 1980s – The decade after independence – the University of Zimbabwe, the very first in the country, was assessed among the best in Africa. He was strongly subsidized by the government with the minor support for donors. At that time, the government also granted subsidies to university students.

Shortly after independence, the country had the most educated workforce and one of the highest literacy rates in southern Africa.

Education demand increased quickly. The government of Robert Mugabe, the president of the time, began to implement an ambitious program in 1996: to build a university in each province in order to fight against colonial inequalities and to expand access to higher education.

But the government lacked resources to fully finance all universities.

In the 1990s, supported by the World Bank and other multilateral institutions, Zimbabwe adopted the second part of an economic adjustment program. The government has reduced spending in public universities and has arrested student subsidies to state establishments.

In 2001, the government had brought costs in post -secondary institutions to help cover costs.

Over time, Zimbabwe’s economic fortune has worsened, further weakening the government’s ability to support its 13 state universities. Over the past decade, the government has reduced the higher education budget, with its share of total public spending of more than half, from 6.9% in 2016 to 3.2% in 2025.

A trembling currency

An unstable monetary system and other economic shocks have made it difficult for public institutions that depend on government financing to operate effectively, explains Godfrey Kanyenze, founding director of the research and economic development research institute in Zimbabwe.

The country, he says, was trapped in an economic instability loop since the Zimbabwean dollar crashed in 1997 and again in 2008.

Although there was a certain stability between 2009 and 2013 after the government introduced a multi-money system, 2018 was a major turning point. That year, the government replaced the US dollars with a new local currency, saying that it was equal to the US dollar. However, the local currency collapsed quickly, destroying people’s savings, increasing prices by more than five times and breaking public confidence in the banking system.

Like many public sector workers, the teachers were seriously affected and they say they never recovered. Vegeyi says that this 2018 move reduced the value of the wages of teachers by almost 90%, from US $ 2,250 per month to US $ 230 per month.

The country has undergone several currency changes since, but the value of the local currency against the US dollar has continued to undertake. At the end of March 2024, the exchange rate had so far dropped that an American dollar has been equivalent to nearly $ 20,000 Zimbabweans. The following month to try to stabilize the situation, the government issued another new currency – nicknamed the Zimbabwean gold – which is partly supported by the government’s gold reserves. But the value has reduced by half since then, and people have mainly used (and prefer) the US dollar.

The government has tried to help civil servants amortize these economic shocks, but the teachers say that the fixes did not help. In January 2020, the government introduced an allowance for officials paid in local currency, ranging from $ 400 Zimbabweans to 800 Zimbabwean dollars per month.

Then in June the same year, the government introduced a monthly allowance of US $ 75. By 2023, the allowances reached around US $ 300 per month.

These allowances were not subject to taxes. However, in 2024, the Government fell to these benefits in regular wages, which means that they would be imposed, which would further reduce employee revenues.

The educational product “is defective”

The current strike at the University of Zimbabwe is only an example of the frustrations accumulated in the country’s universities on the ruin economy.

What many teachers gain now can barely support a fundamental life, undergoing their motivation, says Vegeyi. That, he says, affects the quality of teaching and research.

Although Zimbabwe maintains a strong research production in sub -Saharan Africa, after South Africa and Kenya, quality and impact are low, according to a World Bank 2020 report.

“Without mechanisms of institutional, financial and other support, the product (educational) is defective,” explains Vegeyi. “What quality can come from someone whose children cannot afford health care, food, clothing, education?”

Some teachers have turned to secondary jobs to reach both ends. Some even sell a variety of goods on the campus. “Women use their handbags like Tuckshops,” says Vegeyi. “Some sell vegetables, tomatoes, perfumes and others.”

JT says that chicken farming projects and other small businesses in which he invested when he won well supported it.

Others leave, says Kanyenze.

Precise data is difficult to find, but anecdotal evidence suggests that, as in the health care sector, professionals in the education sector are leaving for better opportunities abroad.

Vegeyi says that since 2018, when wages have dropped, most of the University of Zimbabwe’s departments have lost at least five teachers. In the JT department, 10 out of 18 speakers left for opportunities abroad.

“It is a huge loss for the country,” says Vegeyi. “It is Zimbabwe that passes from resources to training citizens, but other nations benefit from it without spending anything.”

To maintain his workforce, political decision-makers must budge appropriately for all higher education establishments so that they “do not decompose,” says Masunungeure. “The decomposition of these institutions will inevitably lead to the decomposition of the economy and the whole of the national ecosystem.”

‘They have a right’

The prolonged strike was destabilizing, explains Tinotenda Kahenga, a first -year student in pharmaceutical chemistry. “It’s very hard and stressful for me.” Like others among thousands of students enrolled in university, he spent weeks studying alone or with classmates.

But Kohlo, the president of Zimbabwe National Students Union at the University of Zimbabwe, does not blame teachers for having left the students drifting.

“They have the right to fight for fair wages, not the salaries of the slaves they are currently obtaining,” he said, adding that it is the university that is responsible for providing students with an education “in exchange for the exorbitant costs of costs they charge”.

Meanwhile, the student body has repeatedly written to the administration of the disturbance that the strike causes and organized “peaceful demonstrations”, explains Kohlo. The answer? He and six other students were arrested and accused of disorderly driving, although they were released later during the day.