No one wants to file for bankruptcy, but if you’re headed in that direction, delaying the inevitable will only make things worse.

Bankruptcies are still significantly below pre-pandemic levels, but have increased compared to last year. Personal bankruptcies have increased 16% in October compared to a year ago, as more Americans seek debt relief. But those struggling to stay financially afloat should consider this option sooner rather than later, advise experts who study when and why people file.

“When a consumer feels financial pressure, the last thing they think about is filing for bankruptcy protection,” said Michael Hunter, vice president of business development at Epiq Aacer, a provider of bankruptcy information and partner of the American Bankruptcy Institute, or ABI. Most people don’t file until 18 to 24 months after experiencing financial hardship, Hunter said.

Researchers, after surveying thousands of people who have filed for bankruptcy for decades, found that about two-thirds of individual filers struggle to pay their debts for five years before seeking help.

“The common answer is that people have been struggling with their debt for more than two years” before seeking legal recourse, Robert Lawless, a professor at the University of Illinois School of Law, told CBS MoneyWatch .

“People misunderstand bankruptcy and wait too long to see a bankruptcy attorney. Most people would benefit from going sooner,” said Lawless, co-lead investigator in the consumer bankruptcy investigation. Projectlaunched in 1981 by a group of academics, including Sen. Elizabeth Warren, D-Mass., then a law professor.

When to declare bankruptcy

Because of the stigma and shame that Americans attach to bankruptcy, people resort to it as a last resort – often after investing in their retirement funds and other assets that would have been protected from creditors by seeking debt relief. debt.

“If you’re raiding pension funds or other retirement assets, that’s a red flag,” Lawless said, noting that those funds are protected from creditors in bankruptcy. Borrowing money to cover living expenses is another warning sign, he suggested.

“It makes sense to file a lawsuit if a creditor can take something away from you that you need,” said Pamela Foohey, a law professor at the University of Georgia School of Law in Athens. “If someone is facing life-threatening wage garnishment, or if a lender is threatening to repossess your car. If there is no other way to get a car that fits your budget, filing a lawsuit could be a way to keep your car or home.

Otherwise, the general answer is to first think about how they might resolve the cause of their financial difficulties before declaring bankruptcy. “There’s no point in finding a better-paying job if, after a bankruptcy, there are more outflows than inflows,” Lawless said.

“If you lost your job, file your return after finding a new job; if you have a health crisis, you file after you’ve recovered to discharge any medical debts you’ve accrued,” Foohey said.

If a person experiences a change in their family situation, whether it’s a divorce or the birth of twins, she advises them to start by determining how they will manage their budget. after the debt is paid.

“Bankruptcy does one thing: it eliminates debt. He doesn’t get you a job, he doesn’t put money in your pocket,” Lawless said.

Additionally, legally speaking, once the debt is discharged or a financial repayment plan is approved by a judge, it will be another 5-8 years before you can file again.

Chapter 7 vs. Chapter 13

It costs about $1,500 to file Chapter 7, and most attorneys require their fees to be paid upfront. Chapter 7 is a liquidation bankruptcy, in which non-exempt property and assets – property not protected by bankruptcy – are turned over to a trustee and the debt is discharged within 3 to 6 months. According to Lawless, 95% of Chapter 7 members have no assets to return.

With a Chapter 13, payments can be spread out, but the overall cost is much higher.

Having to hire and pay several thousand dollars for an attorney is also a daunting prospect for those who are struggling financially, but Lawless said a lawyer is a better option than declaring bankruptcy yourself or resorting to bankruptcy counseling. consumer credit – a generally for-profit service. and has a long history of problems.

“In Chapter 13, attorneys can’t plan anything in advance, put all of their fees into the repayment plan and charge an average of $4,500,” Foohey said.

According to Foohey, only about a third of those who file for Chapter 13 make it to the end and have their debts discharged. “Not everyone wants discharge, but rather a reset of their relationship with their mortgagee,” she said.

Epiq AACER

A Chapter 13 involves committing to a 3-5 year repayment plan. However, many filers who enter into the agreements do not complete them, Lawless explained. “Owners will file 13 to avoid losing their home. This is part of the tools used to catch up on mortgage payments,” he said.

Lawyers charge much less for Chapter 7 because it is a less complicated process than Chapter 13. The latter is used, but not a good idea, to pay off one’s bankruptcy.

“In 7, you must pay your bankruptcy in advance. In Chapter 13, you pay your attorney on this 3-5 year plan,” Lawless said. “If you use 13 to pay, your attorney feels that’s usually not the right choice.”

According to Lawless, “the first thing Congress should do is make it possible to pay your Chapter 7 attorney over time, so that we don’t have people filing Chapter 13 when they don’t have one.” need. »

Return to pre-COVID numbers

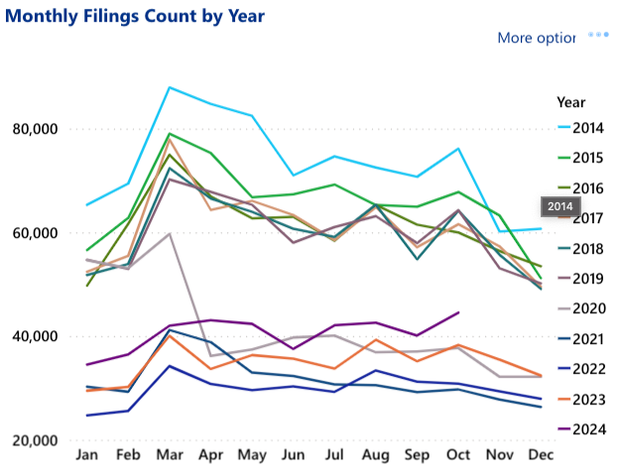

Personal bankruptcy filings averaged about 750,000 per year before COVID-19, but fell during the pandemic, thanks to government assistance.

“It was very consistent from 2014 to 2019 – pretty stable, and then the pandemic hit. A lot of us thought volumes were going to increase,” said Epiq’s Hunter. But there was forbearance on student loans, cars and mortgages, he noted.

“Banks have extended their olive branches and we have seen bankruptcies fall to less than half of pre-pandemic levels,” he said.

“There was a lot of money floating around,” Lawless said, citing government stimulus programs and other aid. “People have paid off their debt,” he said.

Today, with these financial lifelines largely disconnected, American households are adding more debt to their balance sheets. “The biggest surprise is that bankruptcy filings haven’t increased yet,” said Lawless, who expects a return to pre-COVID-19 levels.

Non-commercial bankruptcy filings fell to less than 400,000 before rising to 434,000 in 2023, according to statistics published by the Administrative Office of the United States Courts. With two months to go until the end of 2024, personal bankruptcy filings stood at 405,132 at the end of October.

“We’re still pretty far away from 2019 filing numbers,” Foohey said. “There was a drastic decline at the time of the pandemic that continued for several years, and is now returning to pre-pandemic levels. »